Financial FAQs

A recent column by MarketWatch columnist Rex Nutting shows us why inflation won’t be a problem for maybe years to come. U.S. businesses have become “world class” in squeezing the most from their existing workforce, rather than hiring more workers. This is in part because of the availability of technology to replace workers, but also a mentality that puts profits (and CEO salaries) first. CEO incomes now average more than 400 times the average worker’s salary with stock options and benefits, vs. just 40 times workers’ incomes in past decades.

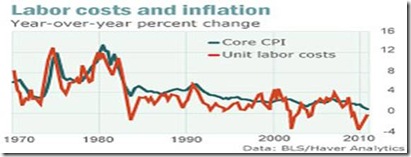

And so labor costs continue to trend downward, which is why inflation is no problem. In 2010, for instance, the first full year of growth after the recession, U.S. total output increased 3.7 percent, reported the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported. But to produce all those extra goods and services, American workers put in just 0.1 percent more hours on the clock. And so labor productivity increased 3.6 percent.

What did we get for that extra effort, asks Rex Nutting? Just a little extra hay: Wages rose 2 percent, but most of that was inflated away. After adjusting for higher prices, real compensation rose just 0.3 percent. If you earned $1,000 a week in 2009, you got the equivalent of $1,003 in 2010, enough for an extra doughnut at the coffee shop.

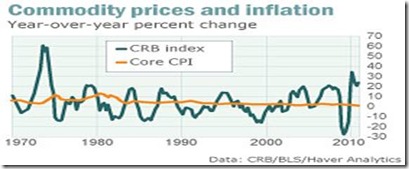

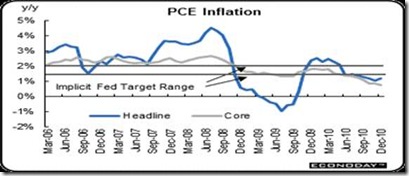

What is making the deficit hawks nervous is that headline inflation—i.e., overall inflation including food and energy prices—has been steadily rising since July, 2010. This is using the Personal Consumption Expenditure price index, which is the best overall measure of domestic prices. But the core rate without food and energy prices hasn’t budged. Why? Because there aren’t enough consumers buying the products and services affected by food and energy prices—such as motor vehicles (though demand for vehicles is rising).

Much of what makes inflation hawks nervous has nothing to do with economic theory, or of common sense. The hawks theorize that if consumers have expectations that prices will increase in the future, they will spend more in the present, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. It is true that when prices are rising, consumers buy more. But which comes first, the horse or cart?

It is only when consumers feel wealthy and their incomes are growing that they create more demand for goods and services, and so drive up prices. Conversely, during recessions when everyone feels less wealthy, consumers hold back driving prices lower. This is the feared Japanese deflationary cycle that has lasted more than 20 years, shrinking the size of Japan’s economy and its citizens’ life styles.

The U.S. has only experienced real deflation during the Great Depression (really 2 depressions back-to-back—1933-37, and 1938-39). And the Federal Reserve knows this. So by pumping more monies into banking reserves with QE2, and holding down interest rates, the Fed is attempting to keep prices within an acceptable range of inflation—1.5 to 2 percent.

Overall inflation trend is still trending downward, as we said last week. The core rate came in unchanged after edging up 0.1 percent in November. On a year-ago basis, headline PCE prices are up 1.2 percent, compared to 1.1 percent in November. Core inflation eased to 0.7 percent year-on-year versus 0.8 percent in November.

Businesses’ costs are the main driver of inflation, and labor is the main cost of doing business. Due to the rapid increase in productivity in 2010 and the pathetic increase in wages, the cost of the labor needed to produce a ton of steel or a loaf of bread fell by an average of 1.5 percent in 2010 after a 1.6 percent drop in 2009.

That is why inflation is still way below the Fed’s ‘implicit’ target range of 1.5 to 2 percent. It is also why the Fed wants to continue with QE2. Right now, the emphasis has to be on creating jobs, and keeping the inflation rate from falling further. For, falling prices mean lower profits for employers, which mean shedding jobs rather than adding them.

The decline in unit labor costs also means businesses aren’t being pressured to raise prices to maintain their profits. In fact, they can cut prices compared with a year earlier and still earn higher profits. They can even afford to give their hard-working employees an extra crumb as a reward.

Most people tend to think inflation comes from higher prices for oil or other commodities, as we said last week. But that’s wrong: Inflation isn’t an increase in a few prices, but rather it’s a general increase in almost all prices across the board. So why don’t we have an inflation problem? Because American businesses are world class at squeezing labor costs — that is, wages, says Mr. Nutting. Unfortunately, the rapid increase in productivity in the American workplace is also keeping millions of willing and able people on the unemployment lines.

Harlan Green © 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment